First African Baptist Church played a central role in the fight for civil rights in Tuscaloosa because it was the home church of Rev. T. Y. Rogers, Jr., the most important local leader in the movement; the primary site for mass protest meetings; and the setting for the most violent local incident, known as “Bloody Tuesday.” It sat next to Van Hoose-Freeman, and Mauldin (now Van Hoose & Steele), a black-owned funeral home founded in 1923 and the longest-running black business in the county.

First African Baptist Church was first established in November 1866 by blacks who rejected the discriminatory practices of First Baptist Church. The founding pastor was a one-time enslaved person, Rev. Prince Murrell. Members initially met in private homes before securing a church building at the corner of 4th Street and 24th Avenue in the black neighborhood of Riverhill. In 1900, they built the current structure at a cost of $25,000. The architecture was inspired by the work of Robert Taylor, a Tuskegee faculty member and the first black person professionally trained and licensed as an architect at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

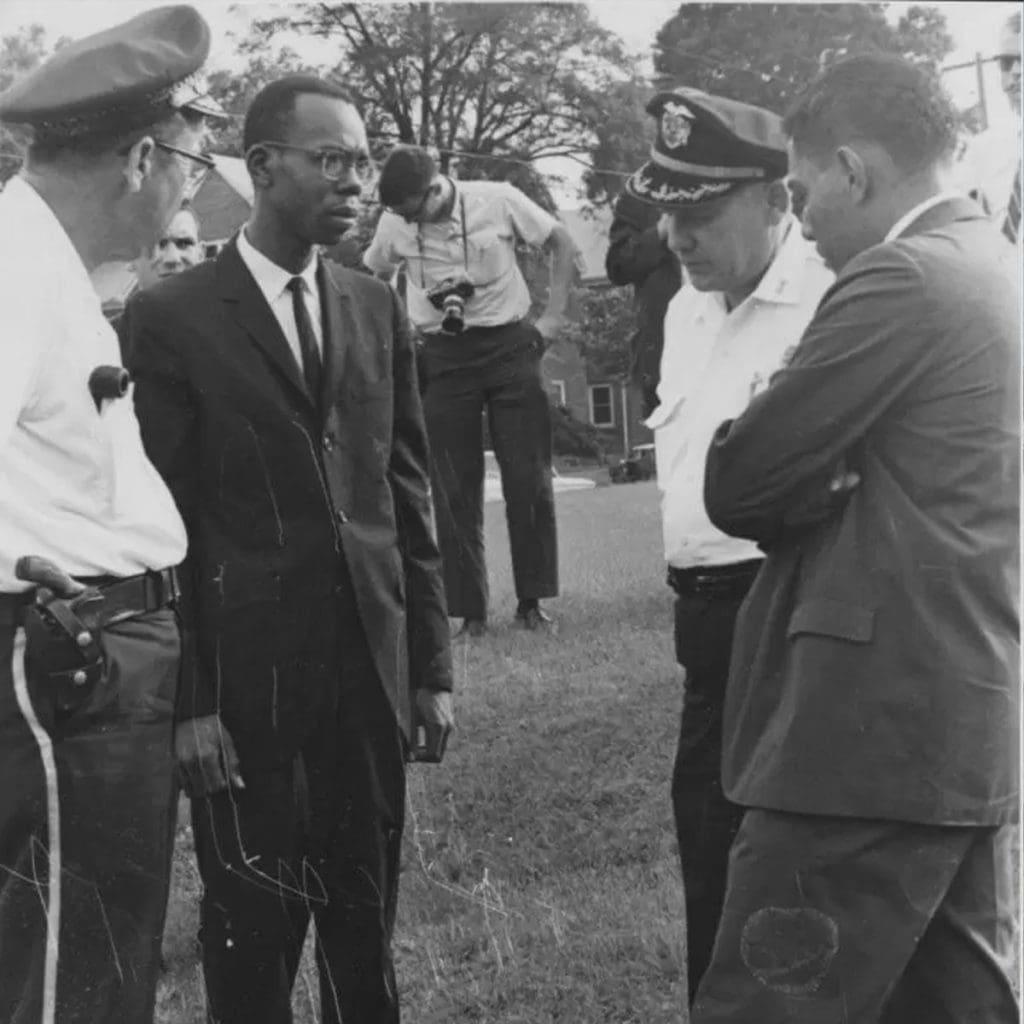

When Rev. T. Y. Rogers, Jr., became the church’s pastor in 1964, Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., delivered the installation sermon. Rogers had studied with King when he was pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery and served as his assistant minister. When a new courthouse for Tuscaloosa was opened in spring 1964, signs separating bathroom facilities and drinking fountains by race were in place despite promises that the facility would be fully integrated. At this point the Tuscaloosa Citizens for Action Committee, of which Rev. Rogers was executive secretary, began organizing the local community to demand that the courthouse became fully integrated. A peaceful march from the church to the courthouse was planned.

On June 9, 1964, a group of nearly six hundred protesters were beaten and tear gassed by the Tuscaloosa Police Department and white extremists. The Fire Department turned a fire hose on the activists as well. Thirty-three protesters were hospitalized and ninety-four blacks were arrested and jailed. The violent incident, which became known as “Bloody Tuesday,” led to a lawsuit filed by the local black community to demand a courthouse free of segregation. On June 26, 1964, federal Judge Seybourn Lynne, citing the 14th Amendment, ordered Tuscaloosa County to remove the discriminatory courthouse signs.